How is it possible we may ask, that after nearly five hundred years we discover a work of one of the best-researched Italian artists; how is it possible that no one had until now paid any attention to it and did not recognize the hand of the divine Michelangelo? In order to answer the question we must travel back to the beginning of the XVI century when the noble Porcari family purchased a chapel in Rome in the prestigious Dominican church, the Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Before her death, Mart Porcari desired to enrich it with new décor and a statue by the rising star of Italian art at that time, namely Michelangelo, who a few years prior gained renown in the Eternal City as the creator of the Pieta (Basilica of San Pietro in Vaticano). When Marta Porcari died in 1512, her initiative was undertaken by the heirs and executors of her will – Matello Vari and Paolo Castellani. Two years later they established contacts with the sculptor, who while he was in the city on the Tiber, was busy with the completion of the funerary monument of Pope Julius II, which was connected with finishing the works as quickly as possible and not undertaking other ones. Michelangelo, who did not refuse any commissions, signed a new contract and agreed to, within four years, complete the figure of a standing nude Christ with a cross in his hand, of natural proportions and according to his own concept, as well as building the appropriate aedicule in the Porcari Chapel. For completing the statue he was to receive two hundred gold ducats. Slowly the artist began his work, using one of the Carrara marble blocks which was designated for the pope's monument. He chiseled out significant parts, but during the processing of the stone, he noticed dark veins in it, which appeared in the worst of places – on Christ's face. He tried to integrate them, lose them in the nasal fold, or hide them in the beard, however finally he gave up – the block did not fit in with his vision. Michelangelo abandoned the unfinished sculpture. He left it in the workshop and then went to Florence where subsequent commissions awaited him.

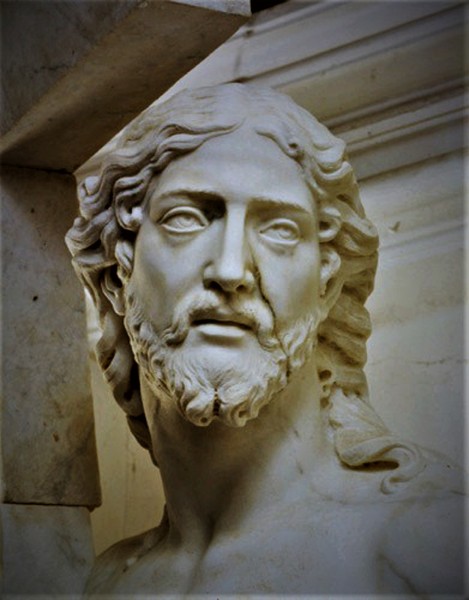

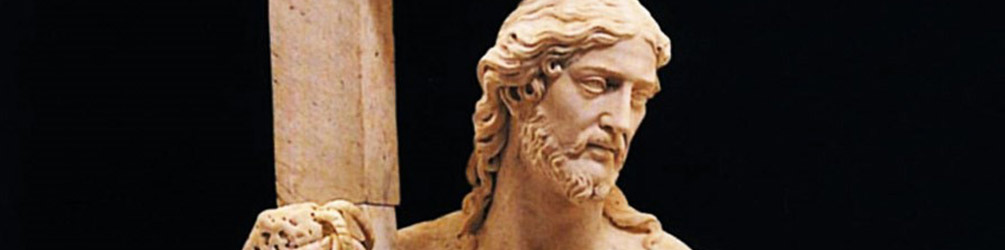

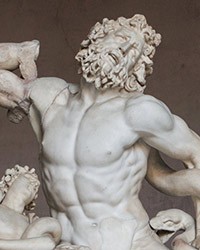

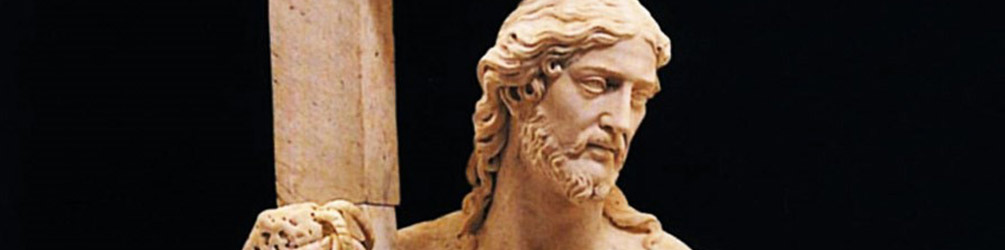

It seemed that he had forgotten about the statue of Christ. He was reminded of it in a letter written by Matello Vari at the end of 1517, gently bringing his attention to the commission. Michelangelo purchased a new block of marble in Florence and began working on another statue similar (undoubtedly) to the images of ancient, muscular heroes, leaning on spears. Thus he referenced the statue of Apoxyomenos found in the Vatican collections – a statue of an athlete sculpted by Lysippos. However, the creation of Michelangelo is much more dynamic. Christ's legs overlap with the Cross, his arm encircles it, and his hips twist gently, while his head – seemingly destroying the compact composition – turns away from the wood of the Cross, as if Christ was searching for something unseen by us. He is holding the Cross with both hands, but in his left hand, we can also see a sponge, a rope, and a long rod – the other attributes of his passion. However, we will not see wounds upon his body. The slight marks on the hands and feet were introduced later – that is why we can have no doubts, that we are witnessing the Risen Christ. He is the one who brings hope of eternal life after death.

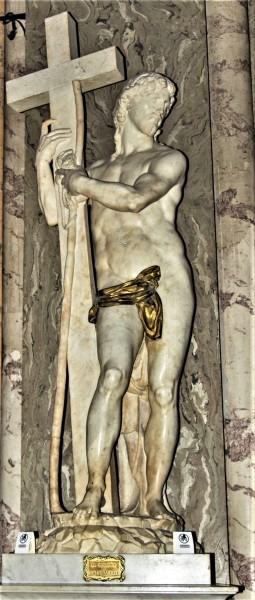

In January 1521, the sculpture was ready, and soon after it was sent by sea to Rome. It was accompanied by Michelangelo's assistant – Pietro Urbano, who was tasked with transporting the figure, finishing the parts not completed by the master, and placing the statue in the aedicule, which was to be completed by another Florentine – Federico Frizzi. As it turned out, Urbano did not manage to complete the task very well, of which Michelangelo was informed in writing. During the transport and finishing works the foot, arm, nose, and chin of Christ were damaged, but ultimately the figure was repaired with the aid of Frizzi. However, that was not the end of it. The Porcari Chapel (left nave, sixth chapel from the entrance) turned out to be too dark and too narrow for the prepared statue. The fact that it was completed by Michelangelo, allowed it, with the consent of the clients and Dominicans, to be moved along with the aedicule, to a more representative location, meaning in front of a column opening the entrance to the apse of the church. At the same time, it was given the appropriate inscription and coat of arms commemorating the Porcari family. In the XIX century, both the epitaph and the aedicule were removed. Today we may look upon the statue of Christ as a free-standing sculpture.

When many years later, Michelangelo finished his last great work – the fresco The Last Judgement adorning the Sistine Chapel (1541) – he was accused of indecency due to the unclothed figures placed on the painting. When the artist died in 1564, his student Daniele da Volterra "dressed" them in robes and loincloths thus gaining the nickname The Breeches-Maker. In art, new times began – of scorn for "the shameless beauty” of the bygone period. The figure of the nude Christ in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva also suddenly seemed provocative, sinful, and indecent. Therefore, the Savior was fitted with a metal loincloth. This was done for decency, but also to hide the lack of genitalia, in a barbaric way hacked off by one of the monks in a fit of sanctimonious rage. This pseudo-loincloth, which we see today – falling and hung in a strange way (?) – is yet another, the most minimalistic of all of the versions of loincloths created in the meantime, which were preserved. Interestingly enough, from the moment the statue acquired the metal loincloth, it became an object of particular veneration by young women, who believed that kissing Christ's foot, would provide aid in finding a husband. An interesting observation was made in 1775 by Marquis de Sade who during his trip around Italy in 1775 noted that Michelangelo gave his Christ too much vigor and strength, which apparently stimulates the faithful to kiss his nude toes to such an extent that they will soon disappear. Adoration of the statue was so intense, that in the XVIII century to save Christ's foot it was covered in a bronze sandal and sock, while in the XIX century during conservation works the kissed-off elements were reconstructed. Presently there is a plate next to the statue which forbids touching it, which is most likely the expression of recognizing its greatness and also that of the name of its creator. However, it is doubtful whether the bizarre knot covering the non-existing genitalia will be removed, despite the fact that it destroys the harmony and the artistic message of this work. Perhaps we will live to see the moment when the aforementioned genitalia will be discovered in the depths of the Dominican monastery. After all, this is not only the work of the divine Michelangelo but also the vitals of God-Man.

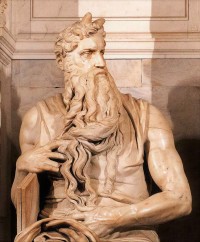

Here, we must answer the question, what happened to the original figure of Christ, the one discarded by the artist in 1515? And this is where the fascinating story of the miraculously discovered statue begins. The sculpture, or more appropriately a block of marble was gifted by the artist to Matello Vari in 1521. This was a kind of gesture to make amends for the long wait or perhaps simply a way to get rid of material that was not fit for further processing. Vari – delighted and proud of receiving such an exceptional gift – in a letter to Michelangelo called this gesture “an honor (so valuable) as if it had been gold”, and sent him a colt in exchange. He placeed the sculpture in his garden near his palace. We do not know how advanced the works on this sculpture were. It may be assumed that it was similar to another block discarded by Michelangelo depicting St. Matthew – meaning an initial phase.

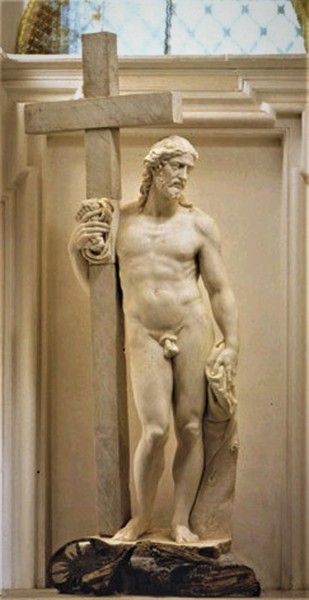

In 1607 the sculpture was sold by Valeri’s heir and ultimately the block, since that is what the sculpture is called in literature, found itself in the possession of an outstanding art collector and expert Vincenzo Giustiniani. And here is where the second, completely unknown, chapter of the story of this work begins. We do not know, which artist worked on it, and how greatly he interfered with the creation of Michelangelo. Unfinished works, such as the greatly admired today Pieta Rondanini (Michelangelo), did not enjoy great esteem at that time. Therefore, it may be assumed, that the well-versed in art marquis ordered the sculpture to be finished in accordance with his own preferences. Certainly, the completely new parts are the right (more delicate) hand, back, and part of Christ's face. Following the spirit of those times, Michelangelo's nude Christ was dressed in a loincloth. Some historians see the resurrected Savior as being completed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini himself. As of now, we have no proof that would confirm such a hypothesis, although that would be some unbelievable news indeed since we would be dealing with a work that was done in cooperation between two of the greatest artists of modern times.

The Christ finished in the XVII century, also referred to as The Giustiniani Christ, is also a veritable ancient hero, leaning on the cross – as if it had been a weapon as well as the tool of salvation. There can be no doubt that this version decisively differs from the statue located in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. It is also more reminiscent of the idea of classical beauty, which is testified to by the harmonious, wavy line stretching from Christ's foot to his arm, as well as the specific heroism of the image.

The third chapter in the story of the sculpture commences in 1638, at the time of the death of marquis Giustiniani. His foster son, Prince Andrea Giustiniani ordered the sculpture to be moved to a church near the monastery of the Sylvestrines in the aforementioned Bassano Romano. The Giustiniani family had its dominion there, including a palace and a summer residence. The Church of St. Vincent Martyr was founded by them twenty years earlier and it was here that marquis Vincenzo desired to be buried. The church was to be a sort of a mausoleum of the family, while the statue was to be put in its main altar. It was preserved in it as a work of an unknown artist, until the seventies of the XX century, to then find its way to the side chapel and finally to the sacristy. There, in 1997, it was discovered by the aforementioned historians (Silvia Danesi Squarzina, Irene Baldriga), and three years later (after long archival studies) they acknowledged it as the lost work of Michelangelo.

Today, once again nude (without the loincloth!), Christ stands inside a narrow, closed-off with grid, for safety reasons, side chapel of the church. It is the pride of the inhabitants of Bassano Romano pleased at the renown that it brought to their town. When asked about its nudity they betray rather contradictory feelings. Some are not bothered by it at all, and others admit to shamefully lowering their gaze when looking at the completely nude body of the Messiah. The custom that holy figures are depicted wearing a loincloth is still deeply rooted within the faithful. This allows us to understand just how revolutionary Michelangelo's work was at the times when he lived, and how open his clients were, but also the Dominicans from the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, who fully knowing that the design of the sculpture assumes presenting the nude figure of Christ, accepted Michelangelo’s vision. We can have no doubt that even then Michelangelo was breaking a taboo but in his creation, he was directly calling upon the Bible. It is within its pages that we will find the description of the body of Christ wrapped in a shroud laid to rest in the tomb, as well as the information that the shroud remained behind at the moment of ascension (Luke 24, 112, John 20,6). The Risen Christ was therefore nude and thus – following the words of the Gospel – was he presented by the divine Michelangelo. And that it was not simply a one-time artistic whim is testified to by the crucifix from the Church of San Spirito in Florence, in which the ingenious artist showed a fully nude Christ upon the cross for the first time. In the statue which we can admire today in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, the artist unclothed Him again. But the original version will probably not be seen there for a long time if ever.

Christ of Minerva (Naked Christ), Michelangelo, 1520, Carrara marble, 205 cm, 1520, Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva

Christ Giustiniani, Michelangelo and unknown artist, 1514 – c. 1610, Carrara marble, Church of San Vincenzo, Bassano Romano

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !